In January 1923, the small Black community of Rosewood, Florida, was obliterated in a week-long spree of racial violence known as the Rosewood Massacre. Triggered by a white woman’s false claim of assault, a white mob, fueled by racial hatred and the Ku Klux Klan’s presence, murdered at least eight Black residents—possibly dozens more—burned the town to the ground, and displaced its entire population. This article in our Racial Crimes series uncovers the horrific events of the Rosewood Massacre, its causes, the gruesome violence inflicted, and the long fight for recognition as we reflect in 2025.

Historical Context: Rosewood in the Early 20th Century

Rosewood, established in the mid-1800s, was a small rural town in Levy County, Florida, nine miles east of the Gulf of Mexico. Named for the pink-hued red cedar trees that once dotted the area, the town thrived on lumber in the late 19th century. White families settled there before the Civil War, with Black landowners arriving in the 1870s after emancipation. By 1886, Rosewood had a post office, a schoolhouse, three churches (one for white residents, two for Black), a general store, a sugar mill, a train station, and even a baseball team, fostering a tight-knit community of about 300 residents by the early 1900s.

The cedar industry’s collapse in the 1890s—after the trees were overharvested—led to economic decline, prompting many white residents to move to nearby Sumner, where a sawmill offered jobs. By 1900, Rosewood had become a majority-Black community, self-sufficient and resilient despite the era’s pervasive segregation. Jim Crow laws, enacted after Reconstruction, enforced racial separation across Florida, restricting Black access to education, jobs, and political power. The Ku Klux Klan’s resurgence after 1915 heightened racial tensions, with Florida chapters growing rapidly by the 1920s. This volatile climate, combined with economic disparities and systemic racism, set the stage for the violence that erupted in 1923.

The Spark: A False Accusation Ignites Violence

On January 1, 1923, in Sumner, James Taylor, a 30-year-old white sawmill worker, left for work, leaving his 22-year-old wife, Fannie Taylor, at home. That morning, neighbors heard screams from the Taylor residence but did not intervene. When James returned, he found Fannie with a large bruise on her face, her lip split and eye swollen shut from a vicious blow. When asked who attacked her, Fannie claimed a Black man had assaulted her, though she couldn’t identify him—a suspicious detail in a small community where most residents knew each other.

Rumors spread quickly, reaching Rosewood. Sarah Carrier, a Black woman who worked as the Taylors’ laundress, was at their home that morning with her granddaughter. She contradicted Fannie’s story, stating she saw a white man—whom she recognized as a frequent visitor—leaving the house. Carrier believed Fannie was covering up an affair, the bruise likely from a domestic altercation with her lover. Despite Carrier’s account gaining traction in the Black community, white residents dismissed it, accepting Fannie’s claim without question—a common practice in the segregated South where a white woman’s accusation against a Black man was rarely challenged.

The white community latched onto a name: Jesse Hunter, a Black man who had recently escaped from a local prison chain gang. With no evidence linking him to the alleged assault, Hunter became the scapegoat. Sheriff Robert Walker organized a posse of white men, deputizing them to hunt for Hunter. The posse borrowed bloodhounds from the prison, intensifying their search, which quickly spiraled into a violent mob mentality.

The Massacre Begins: January 1–2, 1923

The posse first targeted Sam Carter, a 45-year-old Black blacksmith in Rosewood, based on an unconfirmed rumor that he was last seen with Hunter. On January 1, the mob stormed Carter’s home, demanding to know Hunter’s whereabouts. Carter, who had no information, was dragged from his house, a rope tied around his neck, and hoisted onto a tree branch between Rosewood and Sumner. As he gasped for air, his body jerking against the rope, the mob fired bullets into his chest and stomach, blood pouring down his legs as he convulsed and died. They left his mutilated body in the road, a grim warning to the Black community.

Carter’s murder marked the beginning of the massacre. Word of the manhunt spread, drawing white men from neighboring towns—Gainesville, Cedar Key, and beyond—some affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan. By January 2, the posse had ballooned into a mob of 200 to 300 men, armed with rifles, shotguns, and torches, no longer focused solely on Hunter but intent on destroying Rosewood’s Black community.

Escalation and Mass Violence: January 4–5, 1923

Fearing for their lives, Rosewood’s Black residents sought safety in numbers, gathering in homes like that of Sarah Carrier. On January 4, a rumor spread that Hunter was hiding at Carrier’s house, where her son, Sylvester Carrier—a vocal defender of his family—lived with several children from the community. The mob descended on the Carrier home, shooting their dog on sight, its body collapsing in a pool of blood with a yelp. Henry Andrews and Poly Wilkerson, two white men from the mob, kicked down the front door, intent on dragging out Sylvester.

Inside, Sylvester had positioned nine-year-old Minnie Lee Mitchell Langley under the stairway for safety, placing a rifle on her shoulder to steady his aim. When Wilkerson broke through, Sylvester opened fire, bullets tearing through Wilkerson’s chest and Andrews’ head, killing them instantly, their bodies slumping onto the porch in a spray of blood and brain matter. Enraged by the deaths, the mob unleashed a barrage of gunfire into the house, bullets ripping through walls and flesh. Sarah Carrier was struck in the head, her skull shattering as she fell dead, blood pooling around her. Sylvester was hit multiple times in the chest and stomach, his body jerking with each impact before he collapsed, lifeless, his blood soaking the floorboards. The mob only stopped when they ran out of ammunition, leaving the house riddled with holes.

Some children, including Arnett Goins, escaped during the chaos, fleeing to a nearby swamp. Goins later recalled spending two to three freezing January nights in the swamp, hiding among the cypress trees, their clothes torn and skin scratched raw by branches, trembling as they heard the mob’s shouts in the distance. The mob, fueled by adrenaline and hatred, set fire to the Carrier home, the flames consuming the bodies inside, then torched other Black-owned homes and a church, the wooden structures collapsing into piles of ash and embers.

On January 5, the mob—now swelled with Klansmen—returned with renewed fury. They burned the second church, the Masonic lodge, the schoolhouse, and the baseball field, leaving nothing but smoldering ruins. Lexie Gordon, a Black resident, fled her burning home, only to be shot in the back, the bullet severing her spine as she fell face-first into the dirt, blood gushing from the wound as she gasped her last breath. Mingo Williams, a Black man not from Rosewood, was in the wrong place at the wrong time; the mob shot him in the head, his skull exploding in a spray of blood and bone, his body left in the road as the seventh recorded victim.

Escape and Final Destruction: January 6, 1923

By January 6, Rosewood’s Black residents were fleeing en masse, many hiding in the swamp. Those too old or sick to escape, like James Carrier—Sarah’s brother and Sylvester’s uncle, partially paralyzed from a stroke—were hunted down. James, thinking the worst had passed, emerged from the swamp but was cornered by the mob. They marched him to the local cemetery, forced him to kneel beside the fresh graves of Sarah and Sylvester, and shot him execution-style in the back of the head, his brains splattering onto the gravestones as his body slumped into the dirt, blood soaking the ground.

The mob continued their rampage, burning every remaining Black-owned property until Rosewood was completely wiped out. Only one structure survived: the home of John Wright, a white resident who had sheltered Black neighbors during the massacre. White families in Sumner also protected some Black residents they knew, often employees, sparing them from the mob’s wrath.

At 4:00 a.m. on January 6, help arrived via the Rosewood train station—one of the few structures not destroyed. Train conductors John and William Bryce, having heard of the violence, stopped their train to rescue women and children hiding in the swamp. Survivors, shivering and traumatized, boarded the train, which dropped them off in cities like Gainesville, where they started anew, leaving behind everything they owned and living in fear of being hunted down by the mob.

Aftermath: A Community Erased

The Rosewood Massacre left at least eight confirmed dead—Sam Carter, Sarah Carrier, Sylvester Carrier, Lexie Gordon, Mingo Williams, James Carrier, Henry Andrews, and Poly Wilkerson—though historians estimate the true toll could be 27 to 150, as many deaths went unrecorded. The Black community was displaced, their homes, businesses, and generational wealth reduced to ashes. Survivors never returned, some changing their names to avoid being tracked by the mob. The trauma lingered for generations; Arnett Doctor, Sarah Carrier’s great-grandson, recalled family rules forbidding discussion of the massacre unless elders initiated it, a testament to the enduring fear.

In February 1923, a grand jury—all white—reviewed the case but pressed no charges, finding no wrongdoing despite the murders and destruction. No one was arrested, and official records of the massacre mysteriously disappeared, leaving oral histories as the primary source of documentation. The lack of accountability reflected the era’s systemic racism, with all-white juries often biased against Black defendants—a pattern not legally challenged until the 1931 Scottsboro Boys case exposed jury exclusion practices.

Legacy and Recognition: 1990s to 2025

For decades, the Rosewood Massacre was silenced, omitted from history books and public discourse. Survivors and descendants lived with psychological scars, passing down stories of terror. In 1994, after 71 years, Florida acknowledged the massacre through the Rosewood Compensation Bill—the first U.S. legislation to compensate a Black community for racial injustice. Survivors and descendants who could prove property ownership received payments, some as low as $100, a paltry sum critics called an insult. The bill also established a scholarship fund for descendants.

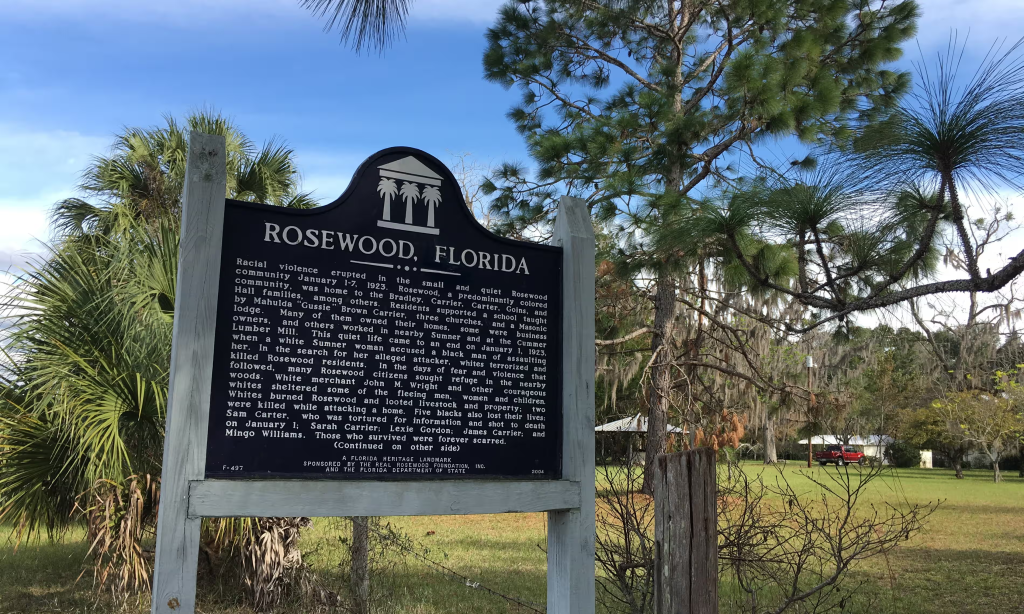

In 2020, Florida created the Rosewood Heritage Foundation, dedicated to researching the massacre and amplifying descendants’ voices. The foundation supports efforts to designate Rosewood as a National Historic Landmark and build museums and exhibits. A historical marker, sponsored by the Real Rosewood Foundation, now stands in Rosewood, detailing the events of 1923. Dr. Edward Gonzalez-Tennant’s Rosewood Heritage and VR Project (virtualrosewood.com) offers a digital archive, ensuring the story endures.

John Wright’s house, the last standing structure in Rosewood, was sold to a private family in 2020. Despite advocacy from the Rosewood Heritage Foundation to preserve it as a monument, its future remains uncertain as of June 2025. The massacre’s echoes resonate in similar events like the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, highlighting a pattern of racial violence in early 20th-century America. This article in our Racial Crimes series calls for continued education and accountability to prevent history from repeating itself.

Sources:

- The New York Times. (1994, May 5). Florida Compensates Victims of 1923 Rosewood Massacre.

- Tampa Bay Times. (2020, January 1). Rosewood Massacre: Florida’s Dark History Remembered.

- Florida Historical Society. (2021). The Rosewood Massacre: A Tragic Chapter in Florida History.

- PBS. (1997). Rosewood: A Town Erased. Documentary.

- University of Central Florida. (2023). Rosewood Heritage and VR Project, virtualrosewood.com.

- The Real Rosewood Foundation. (2022). Rosewood Historical Marker.

- The Guardian. (2020, June 15). Rosewood’s Last House Sold, Sparking Preservation Debate.

- Miami Herald. (1994, April 20). Rosewood Survivors Receive Reparations.

- X post by @WeAreCanProud. (2023, January 6). Rosewood Massacre Anniversary.

- Gonzalez-Tennant, Edward. (2021). The Rosewood Massacre: An Archaeology and History of Intersectional Violence.

- Jones, Maxine. (1997). Documented History of the Rosewood Massacre. Florida State University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.