On September 11, 1942, Alfred Irving, a Black man held in bondage on a Texas farm, became the last documented chattel slave freed in the United States—a stark revelation that challenges the widely accepted narrative that slavery ended with the Civil War in 1865. This case, explored in our Racial Crimes series on DarkCases.com, unveils the grim reality of neoslavery, a system of forced labor and exploitation that persisted through convict leasing, debt peonage, and systemic racial oppression well into the 20th century. As of July 2025, this hidden history remains a critical lens for understanding persistent racial inequalities in America, demanding a reevaluation of the “Standard American History Myth.”

The Foundations of Neoslavery: A Legacy of Legal Entrenchment

The roots of neoslavery trace back to the colonial era, with Jamestown, Virginia, established in 1607, marking the beginning of British colonial slavery in America. Following a workers’ strike in 1619, enslaved Africans replaced indentured servants, setting a precedent for racialized labor exploitation. Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676 prompted Virginia to enact Slave Codes, stripping Black individuals of rights and cementing their status as an underclass. These codes evolved into the Constitution, ratified in 1788, which indirectly protected slavery through the Three-Fifths Compromise, the 1808 slave trade clause, and the Fugitive Slave Clause, ensuring enslaved people could be recaptured even in free states—a direct rebuttal to Britain’s 1772 Somerset case ruling that slavery required positive law.

The cotton gin’s invention in 1793 intensified slavery’s profitability, delaying its anticipated decline. Haiti’s successful slave revolt in 1804 and Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion in Virginia heightened Southern fears, leading to literacy bans for Black individuals, silencing their narratives. By 1860, the Southern economy relied heavily on 4 million enslaved people, with industrial slavery emerging as corporations like railroads owned approximately 20,000 slaves, foreshadowing post-war labor systems.

The Civil War and the Illusion of Freedom

The Civil War (1861–1865) was ostensibly fought to preserve the Union, with Abraham Lincoln initially prioritizing unity over abolition. However, the Confederacy’s secession, explicitly to protect slavery, as articulated by Vice President Alexander Stephens, reframed the conflict. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, unenforceable in Confederate territories, and the 13th Amendment’s ratification in December 1865 formally abolished slavery—except as punishment for crime—yet failed to criminalize its continuation.

Post-war, General Sherman’s Special Field Order 15 in January 1865 promised 400,000 acres of land to freedmen, redistributing 40,000 parcels by June. However, President Andrew Johnson, a white supremacist who assumed office after Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, reversed this in 1865, returning land to white owners and undoing reparations. The Freedmen’s Bureau, established in March 1865 to protect freedmen’s rights, was undermined, setting the stage for neoslavery.

The Rise of Neoslavery: Convict Leasing and Debt Peonage

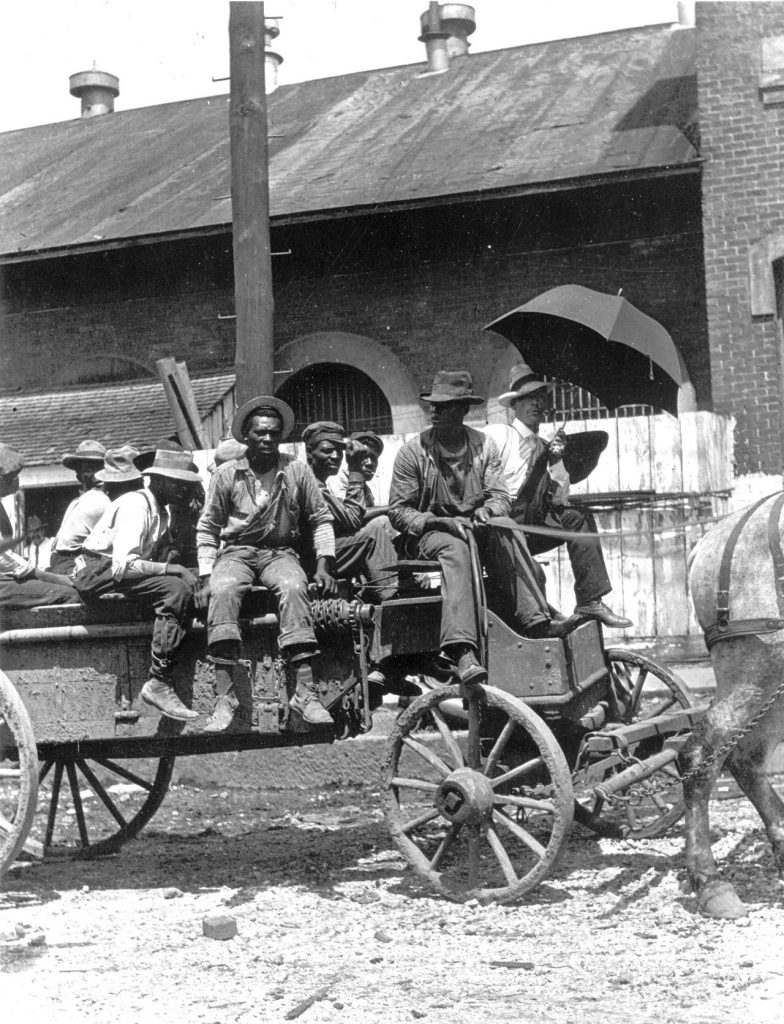

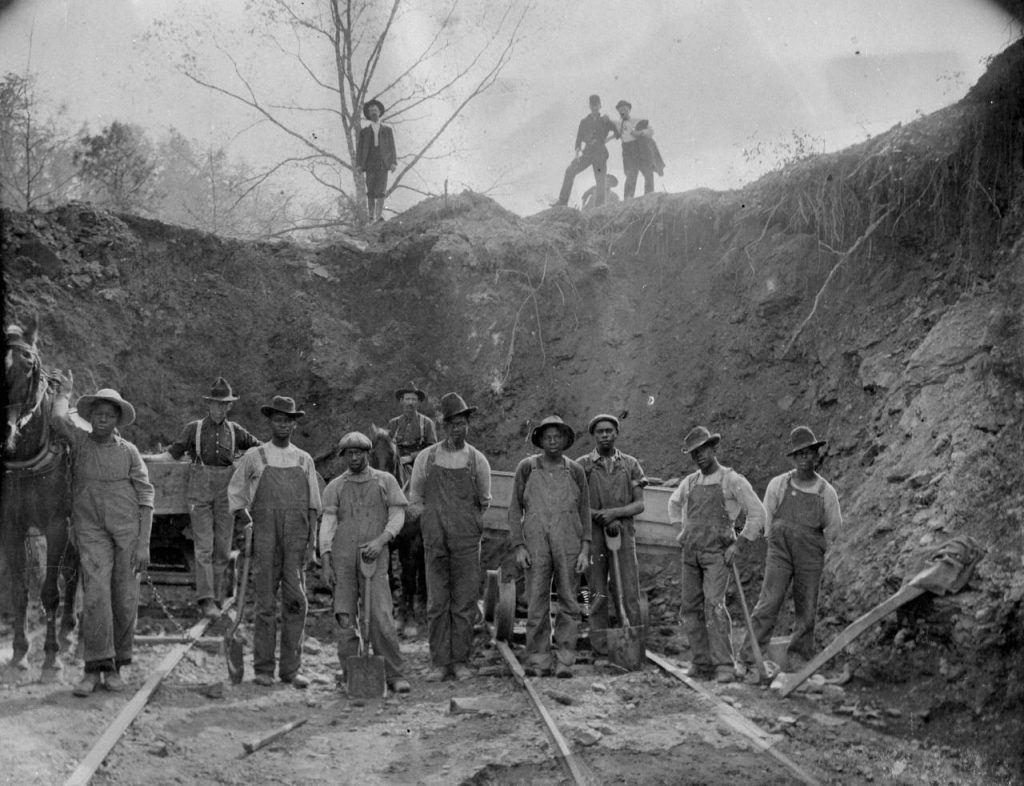

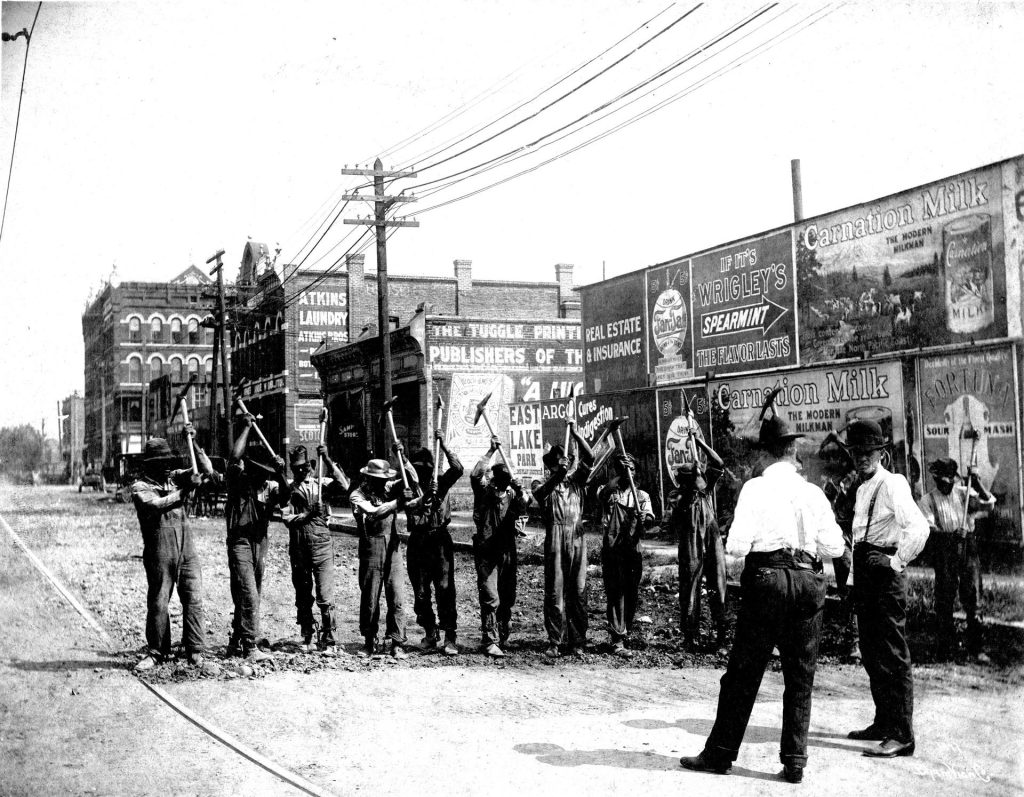

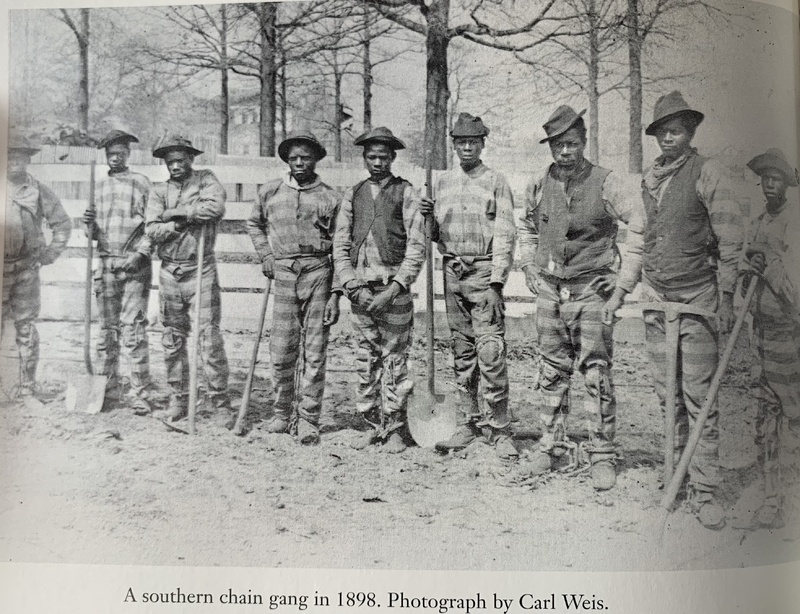

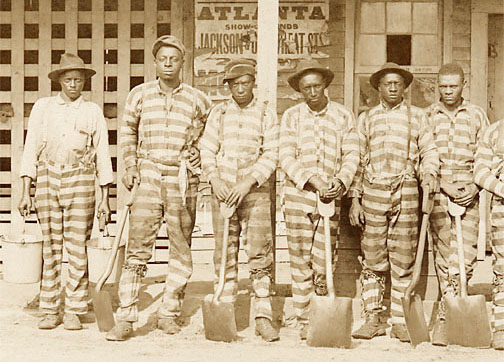

With Reconstruction ending via the Compromise of 1877, federal troops withdrew, allowing Southern states to enact Black Codes—laws ostensibly colorblind but enforced solely against Black individuals. These codes criminalized vagrancy (unemployment), trespassing (walking near railroads), and petty acts like gambling or carrying a razor, targeting the 4 million newly freed Black people. Fines for these “social crimes” led to convict leasing, where states and counties leased prisoners to private entities. By 1866, Alabama and Texas leased hundreds to railroads, while Mississippi returned convicts to cotton plantations.

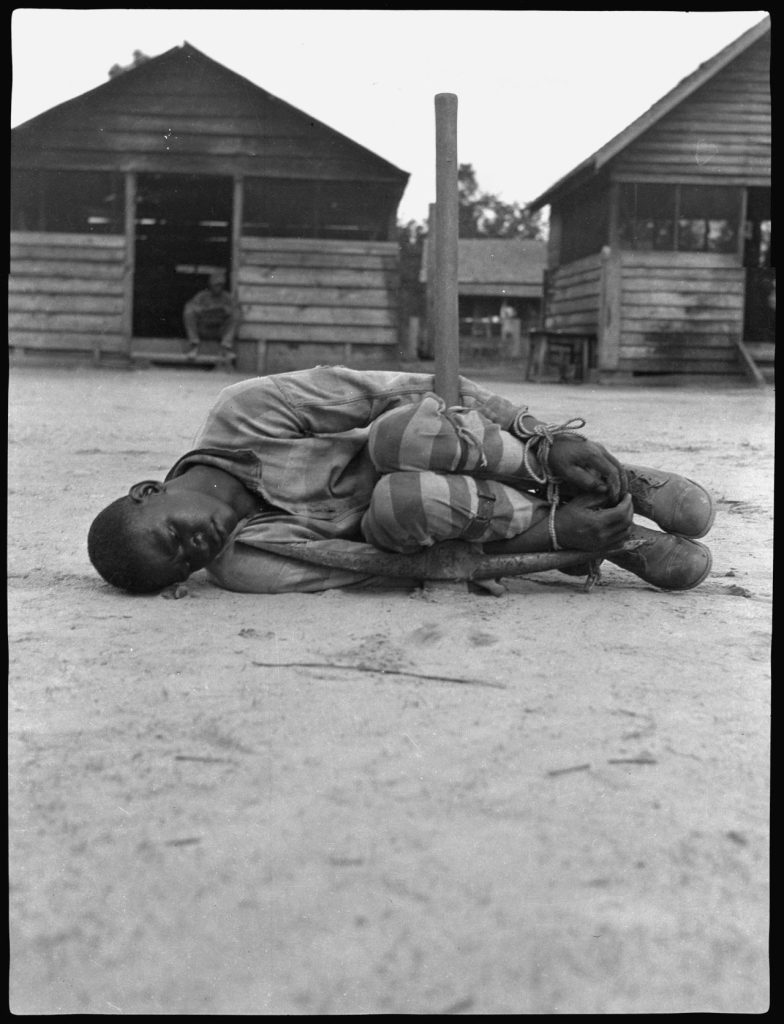

Industrial slavery evolved as companies like Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Rail, founded on Confederate slave labor, leased over 1,000 convicts by 1900, with a 30% annual death rate in mines like Coalburg. Green Cottenham, arrested in 1908 for vagrancy, died after five months of brutal labor. Debt peonage complemented this, where individuals, unable to pay fines, were coerced into labor contracts with escalating debts, as seen in John Davis’s case in 1901, where he was sold between farmers after a fabricated charge.

The judicial system, lacking public defenders until 1964, relied on Justices of the Peace—often plantation owners—who guaranteed convictions. Plea bargaining emerged as a survival tactic, with “not given” charges reflecting arbitrary guilt. The Department of Justice’s 1903 investigation into John W. Pace’s slavery ring in Alabama exposed a network holding hundreds in “involuntary servitude,” yet charges were dismissed due to the 13th Amendment’s lack of criminal penalties for slavery.

Persistence and Public Outrage

By 1909, Georgia abolished convict leasing after public hearings, but Alabama persisted until 1928, leasing 37,000 prisoners, many for alcohol-related offenses during Prohibition. Martin Tabert’s 1921 death in a Florida turpentine camp, a white man from North Dakota, sparked national outrage, ending Florida’s program in 1923. Chain gangs emerged in the 1920s and 1930s for state projects, while county-level leasing and debt peonage continued unchecked.

Legal setbacks like the 1883 Civil Rights Act ruling and the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision entrenched segregation. The Lost Cause narrative, amplified by the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, revived the Ku Klux Klan, while eugenics and Manifest Destiny justified racial hierarchies. The Negro Motorist Green-Book (1936–1966) highlighted ongoing hostility, reflecting a society where Black individuals risked lynching or disappearance.

World War II exposed this hypocrisy. In December 1941, FDR’s Justice Department, via Circular 3591, redefined peonage as “involuntary servitude and slavery,” prompting prosecutions. Alfred Irving’s 1942 liberation from the Skrobarcek family in Texas, who starved and beat him for four years, marked the end of chattel slavery, though systemic oppression persisted through segregation (ended 1964) and the War on Drugs (initiated 1971), which disproportionately targeted Black communities.

Unresolved Injustices

Neoslavery is a continuum of oppression—from Slave Codes to Black Codes, convict leasing, debt peonage, and mass incarceration—explaining racial disparities in education, income, and criminal justice. The absence of reparations, despite historical precedents like Special Field Order 15, underscores governmental responsibility. As of 2025, this history, omitted from standard curricula, challenges the narrative of a post-racial America, urging a reckoning with systemic racism’s enduring impact.

Sources:

- National Archives. (n.d.). The Constitution of the United States. Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript

- Library of Congress. (n.d.). African American Odyssey: The Civil War. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html

- Douglas A. Blackmon. (2008). Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Anchor Books.

- U.S. Department of Justice. (1903). Report on Convict Leasing and Peonage in Alabama. Historical Records Division.

- Equal Justice Initiative. (2013). Slavery in the 20th Century. Retrieved from https://eji.org/reports/slavery-in-america/

- PBS. (2003). The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. (n.d.). Reconstruction and Its Aftermath. Retrieved from https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/reconstruction-and-its-aftermath

- National Park Service. (n.d.). Special Field Orders, No. 15. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/articles/special-field-orders-no-15.htm

- The New York Times. (1942, September 12). Texas Family Convicted in Slavery Case. Archives.

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (n.d.). Documenting the American South: Black Codes. Retrieved from https://docsouth.unc.edu/

- Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. (n.d.). The Negro Motorist Green-Book. Retrieved from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/collection/negro-motorist-green-book

- History.com. (2020). Convict Leasing. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/convict-leasing

- U.S. House of Representatives. (n.d.). The 13th Amendment. Retrieved from https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1851-1900/The-13th-Amendment/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.