In the early hours of June 1, 1918, the Cabiness family of Walker County, Texas, faced a horrific end when a mob of white men, led by Sheriff Thomas E. King, descended upon their home, resulting in a massacre that erased an entire lineage built from the ashes of slavery. Featured in our Racial Crime series, this tragedy, often overshadowed by history, exposes the brutal enforcement of Jim Crow laws and racial terror.

The Cabiness Family: A Family Forged Through Adversity

The Cabiness family’s story begins in 1845 when Samuel Calhoun, a white slave owner from South Carolina, relocated to East Texas, drawn by the fertile lands along the Trinity River near Huntsville. Among his enslaved property was 13-year-old Elijah Cabiness, forcibly transported alongside other enslaved Black individuals owned by the Calhoun and Cabiness families. Historical accounts, such as those from John McAdams, a formerly enslaved man from Walker County, describe the grueling life of enslaved people in this region—working from dawn until after dusk, tending fields, cattle, and livestock with no respite.

Elijah’s emancipation came with the 13th Amendment in 1865, yet freedom brought little relief. As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. later noted, it was “freedom to hunger” and “freedom to the winds and rains of heaven,” lacking land or resources. Post-emancipation violence in Walker County was rampant; on the day freedom was announced in Huntsville, a Black woman was brutally murdered by a white man angered by the celebrations. Despite this, Elijah persevered, registering to vote in 1867 under federal protection, a rare achievement for a formerly enslaved man.

By 1870, Elijah married Caroline, though her fate remains unclear after 1871. He then wed Evelyn Calhoun, and they settled in Grant’s Colony, East Texas, where Elijah’s farming success secured crop loans in 1872, 1875, and 1878. Owning 160 acres valued at over $1,000 by 1880, he supported his children, purchasing 157 acres for his son Allan in 1883. Allan married Sarah Carter, and they had eight children, including Sam Norman (b. 1884). Despite their 1907 divorce—marked by contentious allegations—Sarah raised their children on the family land, listed as head of household in the 1910 census with six children, including George (b. 1897).

The Spark: George Cabiness and the Draft Controversy

The family’s stability began to fall apart in 1917 amid World War I. The Selective Service Act mandated draft registration for men aged 21–31, and Clifton (24) and Tanola (22) complied. However, Sheriff Thomas E. King falsely accused George Cabiness, aged 20, of draft evasion, claiming school records listed his birth as 1894, making him 23. Despite Sarah’s protests and the family’s prior compliance, King, supported by U.S. Marshal J.A. Herring, pursued federal charges on July 14, 1917.

This reflected a broader pattern of racial bias in the draft. Black men were nearly three times more likely to face prosecution for evasion, with 34% drafted compared to 24% of white men, despite comprising just 16% of Texas’s population. Texas authorities aggressively targeted Black men, often ignoring exemptions, as seen in cases like Andrew Felder (jailed four months in 1918) and George Johnson (held five months post-war). George’s arrest and Sarah’s detention for “conspiring” highlighted this systemic targeting.

After a two-month detention, a federal grand jury on October 2, 1917, cleared George and Sarah, attributing the discrepancy to absent birth records—a common issue for Black families reliant on church or family documentation. Yet, their exoneration fueled local white resentment, viewing George’s freedom as a challenge to racial hierarchy.

The Massacre: A Brutal Retaliation

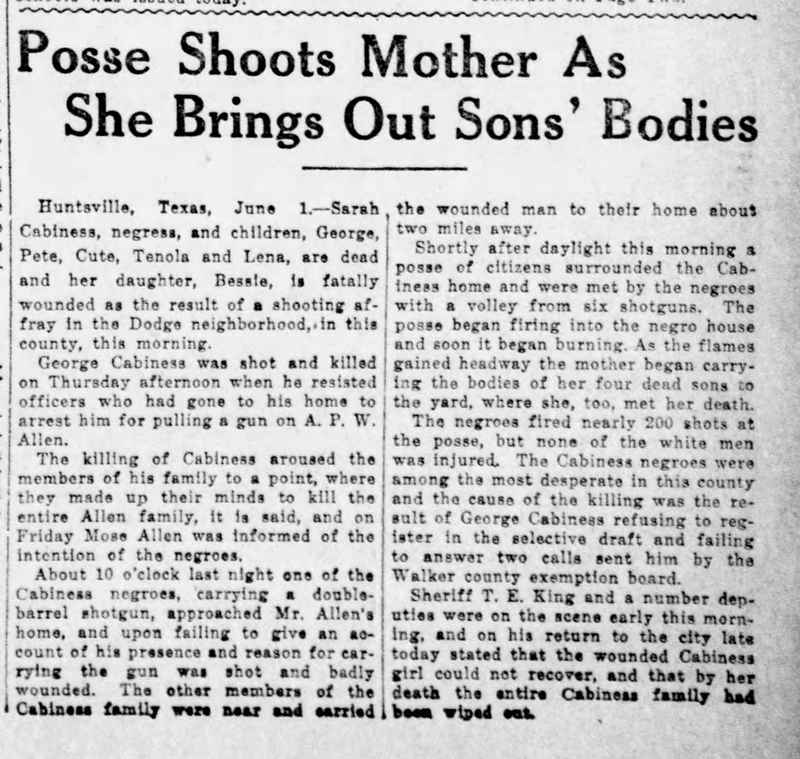

Tensions escalated on May 31, 1918, when George, tired of harassment, clashed with Alvin P. Allen—Sheriff King’s father-in-law—after Allen threatened re-arrest. George’s self-defense with a weapon, a rare act of resistance, enraged the white community. Sheriff King and his men descended on the Cabiness home that night, killing George under disputed circumstances—reports claimed resistance, but inconsistencies suggest execution.

The next day, June 1, a mob, including Moses Allen, Tom Holland, Sam Roark, James Jones, and King, attacked again. Official accounts alleged the family fired over 200 rounds with six weapons, igniting the house in self-defense, killing Sarah execution-style as she fled with her children. However, Bessie Cabiness, injured but surviving, later told the NAACP that the mob initiated the attack, burned the house, and prevented escape, contradicting the press narrative of family armament.

The mob arrived at dawn, surrounding the Cabiness home in a premeditated ambush. Unarmed, the family was met with a barrage of gunfire, bullets ripping through wooden walls and shattering windows, striking multiple family members in the chaos. Sarah, attempting to shield her children, was shot in the back as she dragged them toward the door, her body crumpling in a pool of blood on the porch. The mob then doused the house with kerosene, the acrid fumes filling the air before flames erupted, consuming the structure and trapping the remaining victims inside. Screams echoed as the fire roared, the wooden frame crackling and popping, black smoke billowing into the sky while the mob watched, ensuring no escape. Bodies burned beyond recognition, charred flesh peeling from bones, the stench of seared human remains lingering for days. Pete Cabiness’s body, dragged from the Allen home the previous night and riddled with bullets, was thrown back into the inferno, his corpse twisted in the heat.

The assault lasted mere minutes but felt eternal to survivors like Bessie, who crawled through the smoke-filled chaos, bullets grazing her head, chest, arms, and back, leaving her body riddled with wounds and crippled for life. She fled to Galveston for treatment, her escape a miracle amid the carnage. The massacre claimed Sarah, George, Pete, and other family members, their deaths a calculated erasure of Black prosperity.

Bessie, wounded in the head, chest, arms, and back, escaped to a Galveston hospital, crippled but alive. Her 1919 statement exposed the mob’s premeditated violence, yet the NAACP’s efforts faltered. Bessie died of tuberculosis in February 1920 in Baltimore, silencing the truth. No one was prosecuted; King died in 1948, Allen in 1928, and Moses Allen in 1963, living unpunished lives.

Unresolved Injustice

The Cabiness Massacre, with over 260 lynchings in Texas from 1889–1918, exemplifies Jim Crow’s racial terror. Elijah’s journey from slavery to landownership was obliterated, his descendants erased for daring to assert their rights. The NAACP’s failed intervention and Governor Hobby’s inaction reflect a society where Black lives were expendable. This case underscores the need to remember such atrocities, ensuring the Cabiness family’s story endures against historical erasure.

Sources

History.com. (2020). Jim Crow Laws. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws

Texas State Historical Association. (n.d.). Walker County, Texas. Retrieved from https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/walker-county

National Archives. (n.d.). World War I Draft Registration Cards. Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww1/draft-registration

Equal Justice Initiative. (2015). Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. Retrieved from https://eji.org/reports/lynching-in-america/

Library of Congress. (n.d.). The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Black Freedom. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war-glass-negatives/articles-and-essays/reconstruction-and-its-aftermath/

Houston Chronicle Archives. (1918, June). Reports on Cabiness Incident. Historical Records.

NAACP Records. (1919). Correspondence on Cabiness Lynching. Retrieved from https://www.naacp.org/history/

U.S. Census Bureau. (1910). Walker County, Texas Census Records. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.