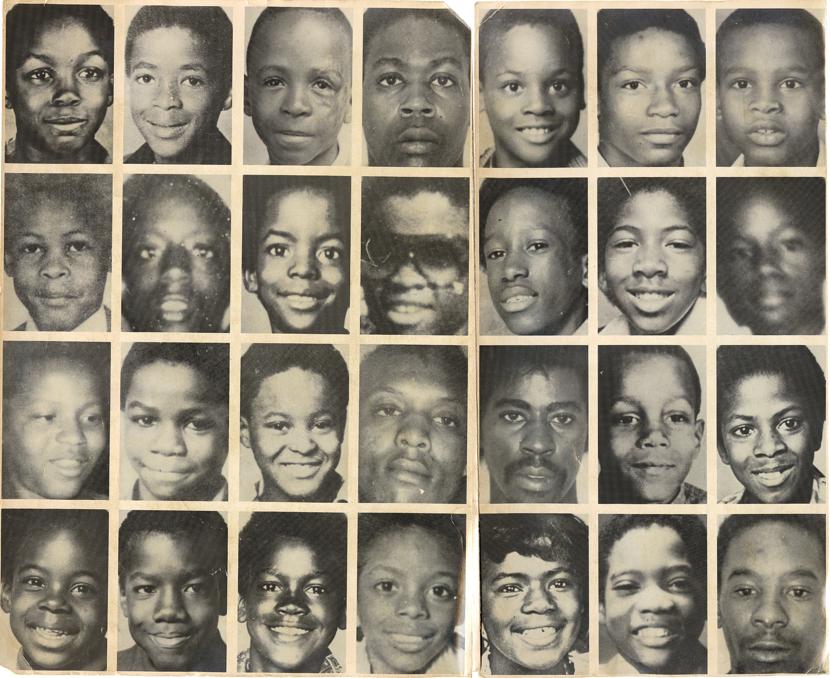

In the sweltering summer of 1979, Atlanta, Georgia, became the stage for a nightmare that would haunt its streets for years. The discovery of two murdered Black boys—Edward Hope Smith and Alfred James Evans—on July 28 marked the beginning of the Atlanta Child Murders, a series of killings that claimed at least 28 young lives, mostly Black children and teens, between 1979 and 1981. As of June 2025, this case, explored in our Serial Killer Cases series, remains a painful chapter of unresolved grief, racial tension, and a city’s struggle for justice.

A City on the Rise, Shadows Within

By the late 1970s, Atlanta was transforming into “the city too busy to hate,” a beacon of the New South with economic growth and cultural prominence. The city’s metropolitan expansion attracted businesses and diverse residents, while milestones like the election of its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973, and the appointment of Black leaders in public safety signaled progress. Yet, beneath this facade, systemic racism persisted, with Black Atlantans facing discrimination in housing, jobs, and policing. This backdrop set the stage for a tragedy where the deaths of Black children were initially dismissed as drug-related violence, a response that would fuel community outrage as the body count rose.

The Murders Begin

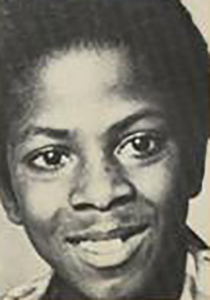

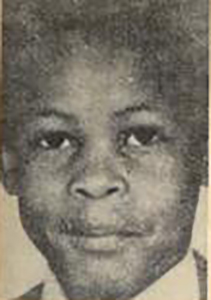

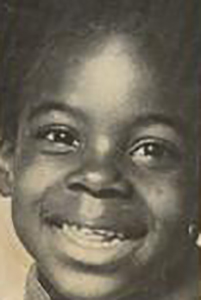

The horror surfaced on July 28, 1979, when a woman collecting cans off Niskey Lake Road stumbled upon the decomposing body of 14-year-old Edward “Teddy” Hope Smith, killed by a .22-caliber gunshot to the back. Nearby, within 150 yards, lay 13-year-old Alfred James Evans, dead from strangulation, his body so decayed it took over a year to identify. Both boys, from low-income Black neighborhoods, had been missing for a week, but police resisted linking the cases. The reluctance deepened as more children vanished: 14-year-old Milton Harvey, last seen riding his bike to pay a bill, was found two months later, skeletal remains offering no clear cause of death; 9-year-old Yusuf Ali Bell, abducted after buying snuff, was discovered strangled in an abandoned school’s crawlspace, with green carpet fibers on his pants marking a critical clue.

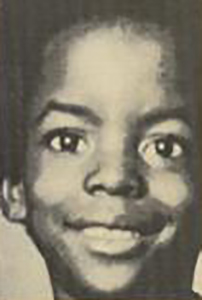

By mid-1980, the toll mounted. Angel Lenair, 12, was found tied to a tree with women’s underwear in her mouth; Eric Middlebrooks, 14, was bludgeoned behind a bar; Christopher Richardson, 12, disappeared en route to a pool; 7-year-old Latonya Wilson was taken from her home; 10-year-old Aaron Wyche fell from an overpass; and 9-year-old Anthony Carter was stabbed behind a warehouse. Eleven children were gone, eight dead, and the community’s fear grew palpable.

A Community Fights Back

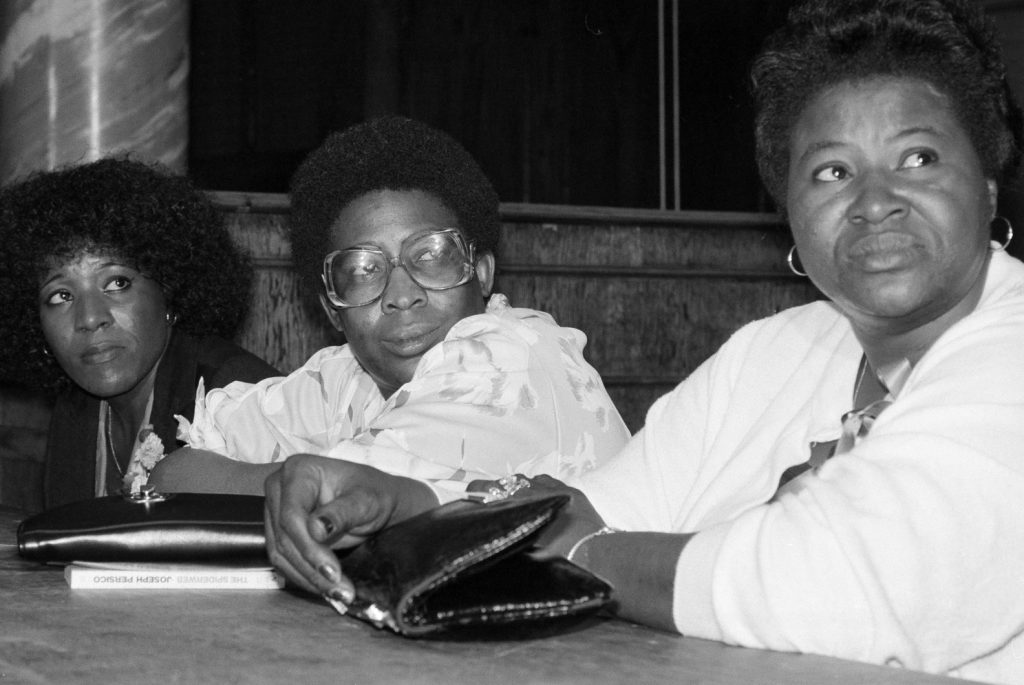

Frustration boiled over as police minimized the crisis. Camille Bell, Yusuf’s mother, refused to accept the “runaway” label, forming the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP) with Willie Mae Mathis and Venus Taylor in June 1980. Their relentless advocacy—pleas on TV, marches to City Hall, and neighborhood watches—forced action. In July 1980, Public Safety Commissioner Lee Brown established a Special Task Force, later expanded to 17 officers, with FBI assistance. Yet, the killer persisted, claiming Earl Terrell, 10, found after a ransom call; Clifford Jones, 12, strangled beside a dumpster; and Darron Glass, 11, never found.

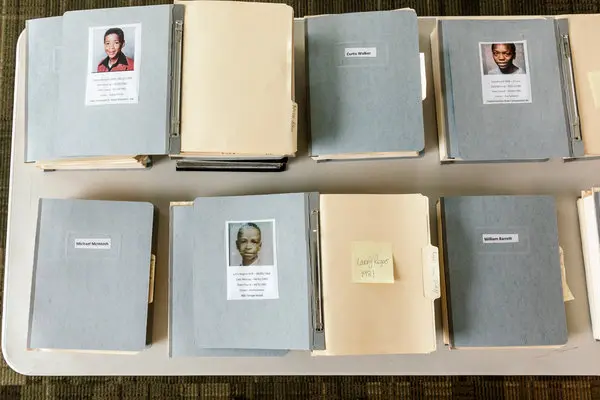

The murders escalated in 1981, shifting to rivers as the killer adapted to fiber evidence leaks. Lubie Geter, 14, Terry Pue, 15, Patrick Baltazar, 12, Curtis Walker, 13, Joseph Bell, 15, and Timothy Hill, 13, were among those strangled, their bodies often stripped or marked with fibers. Adults like Eddie Duncan, 21, and Larry Rogers, 20, were added to the list, intensifying the crisis.

The Investigation Unfolds

The investigation into the Atlanta Child Murders was a complex, often faltering effort marked by initial resistance, evolving tactics, and persistent dead ends. When Edward Smith and Alfred Evans were found in July 1979, Atlanta police treated the cases as isolated, attributing them to drug-related violence despite the boys’ ages and the proximity of their bodies. This reluctance persisted as Milton Harvey’s skeletal remains and Yusuf Bell’s strangled body emerged, though the discovery of green carpet fibers on Bell’s pants in November 1979 hinted at a pattern. Investigators initially dismissed this clue, lacking the forensic expertise to pursue it, and no centralized effort was made to connect the cases.

Pressure from STOP and the community forced a shift. In July 1980, the Special Task Force was formed, initially with five officers, tasked with identifying links across the murders. The team, led by detectives like Chet Dettlinger, began compiling a victim list, though its criteria—based on public pressure and media attention rather than scientific rigor—later drew criticism. The task force sought FBI Behavioral Science Unit support, which introduced profiling techniques, suggesting a single killer targeting vulnerable Black youth. However, early efforts stalled, with only 14 of 21 cases by February 1981 yielding suspects, and many leads, like a shopping plaza manager seen with Clifford Jones, were dropped due to witness credibility issues.

A turning point came with Earl Terrell’s disappearance in July 1980, when a ransom call prompted federal involvement. The FBI joined the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) and Atlanta PD, deploying agents to analyze phone records and canvass neighborhoods. The task force expanded to 17 officers, working round-the-clock, but progress was slow. The discovery of Terrell and Richardson’s remains together in January 1981 suggested coordinated dumping, yet no cause of death was determined due to decomposition.

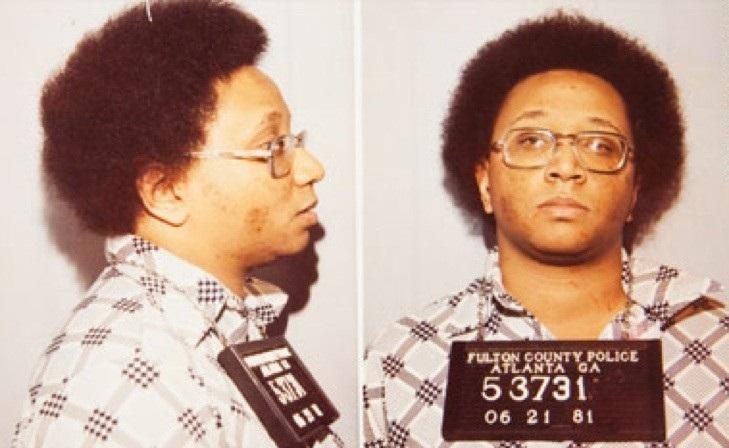

As murders intensified in 1981, the investigation adapted. The leak of fiber evidence to the Atlanta Constitution prompted a shift to river dumps, leading to a massive FBI stakeout in May 1981. Monitoring 14 bridges with 72 officers, the operation culminated on May 22 when recruits heard a splash near the James Jackson Parkway Bridge, leading to Wayne Williams’ stop. Though no body was found that night, Nathaniel Cater’s emergence downstream two days later tied Williams to the case. Subsequent searches of his home yielded carpet samples, dog hairs, and blood stains, analyzed by the FBI’s forensic team. Fiber matches to Wellman Inc. carpets and dog hairs from Williams’ German Shepherd linked him to multiple victims, though the evidence remained circumstantial.

The GBI’s secret probe into KKK involvement, initiated in February 1981, uncovered wiretapped conversations hinting at racist plots, but this was sidelined after Williams’ arrest. The task force’s focus narrowed to him, closing 23 cases without trials, a decision that fueled ongoing debates. Retired officers and journalists later highlighted oversights—unlisted victims like Faye Yearby, continued killings post-conviction, and the arbitrary victim list—leaving the investigation’s completeness in question as of June 2025.

The Wayne Williams Case

The breakthrough on May 22, 1981, when a stakeout caught Wayne Bertram Williams, 23, after a suspicious splash, shifted the investigation’s focus. Though no body was immediately found, Nathaniel Cater, 27, surfaced downstream two days later, asphyxiated. Fibers from Williams’ home carpet and dog hairs from his German Shepherd matched evidence on victims, leading to his arrest on June 21, 1981. His trial, starting January 6, 1982, hinged on circumstantial evidence—fibers, blood stains, and eyewitness accounts linking him to Cater and Jimmy Ray Payne, 21. On February 27, 1982, he was convicted, receiving two life sentences.

Questions and Legacy

John Bazemore/ap

The conviction closed 23 cases, but doubts linger. Many, including Camille Bell, rejected Williams as the sole killer, citing weak fiber evidence and unaddressed cases like Faye Yearby’s. Theories of KKK involvement, supported by GBI wiretaps of racist plots, were abandoned as Williams became the focus. Critics, including retired officer Chet Dettlinger, argue the victim list was politically curated, with murders continuing post-conviction. James Baldwin’s “The Evidence of Things Not Seen” captures the city’s rush to resolve a crisis, leaving families without full closure. As of June 2025, the Atlanta Child Murders remain a haunting enigma, a testament to lost lives and a community’s enduring fight.

Sources

- Atlanta Police Department archives and task force reports (1979-1981).

- FBI case files and statements on the Atlanta Child Murders.

- Atlanta Journal-Constitution historical coverage.

- WSB-TV news archives and Sam Ford reports.

- Chet Dettlinger, “The List” (1981).

- James Baldwin, “The Evidence of Things Not Seen” (1985).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.