In the summer of 1919, America experienced a wave of racial violence known as the Red Summer, marked by riots, murders, and arson across 26 cities. Fueled by deep-seated racism, economic tensions, and the return of Black World War I veterans, the violence claimed hundreds of lives—estimates range from 100 to over 1,000—and left communities devastated. This article in our Racial Crimes series explores the Red Summer’s causes, pivotal events in Washington D.C., Chicago, and Elaine, Arkansas, and the enduring legacy of this dark chapter in U.S. history as we reflect in 2025.

Historical Context: A Nation on Edge

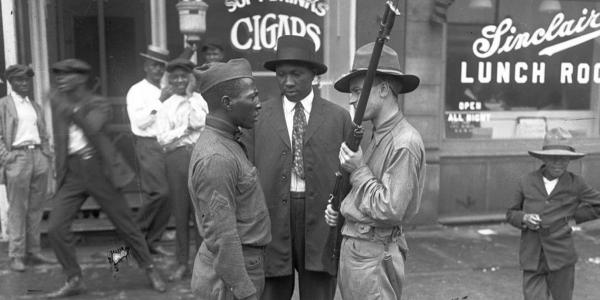

The Red Summer of 1919 emerged from a volatile post-World War I America. The Great Migration, beginning around 1910, saw six million Black Americans flee the South’s oppressive Jim Crow laws, lynching threats, and the Ku Klux Klan’s resurgence for better opportunities in Northern and Midwestern cities. By 1919, this migration had swelled Black populations in urban centers, intensifying racial tensions as white communities resisted integration. The war’s end in 1918 brought Black veterans home expecting equality for their service, but they faced hostility instead, amplifying a climate ripe for violence.

Economic disparities added fuel to the fire. The post-war economic boom benefited landowners and factory owners, while sharecroppers and industrial workers—many Black—saw little gain. In the South, cotton prices quadrupled from 11 cents to 44 cents per pound, yet sharecroppers were systematically cheated out of fair wages. Meanwhile, the Russian Revolution of 1917 sparked fears of communism in the U.S., with propaganda linking Black activism and unions to a supposed communist threat, heightening paranoia among white authorities.

The Spark: Racial Tensions Ignite

The Red Summer’s violence was not spontaneous but built on systemic racism. President Woodrow Wilson, elected in 1912 with significant Black voter support due to his “new freedom” promises, quickly disappointed by allowing federal segregation. Within weeks of his inauguration, his postmaster general proposed extending Jim Crow policies to government workplaces, isolating Black employees—some even caged at their desks—and halting their economic progress. W.E.B. Du Bois of the NAACP condemned this as treating Black Americans “as if mere contact with them were contamination.”

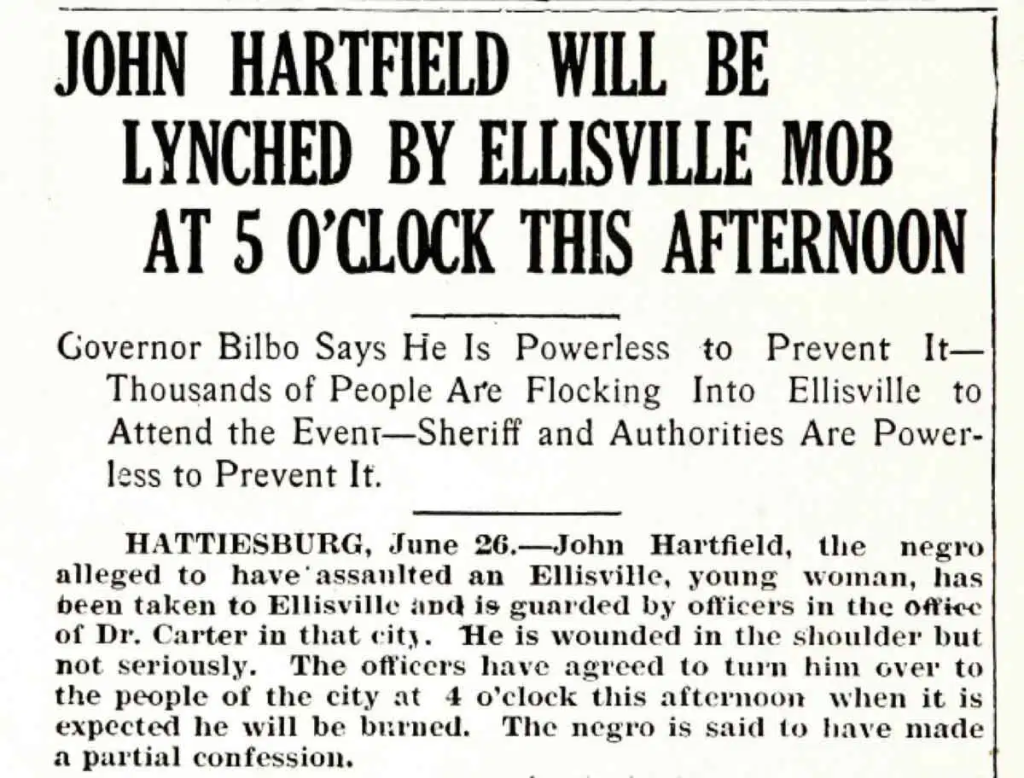

Newspapers exacerbated tensions with sensationalized stories. In Washington D.C., The Washington Post on July 19, 1919, falsely reported a Black man, Charles Ralls, attacked a white woman, Elsie Stephnick, sparking outrage. In Chicago, the July 27 death of 17-year-old Eugene Williams—drowned after white beachgoers threw rocks at him, one striking his head with enough force to knock him unconscious and leave him bleeding into the water as he sank—ignited fury. In Elaine, Arkansas, the September 30 union meeting of sharecroppers planning to sue for fair pay was framed as a communist plot, setting the stage for bloodshed.

Key Events: Violence Across Cities

Washington D.C.: July 19–21, 1919

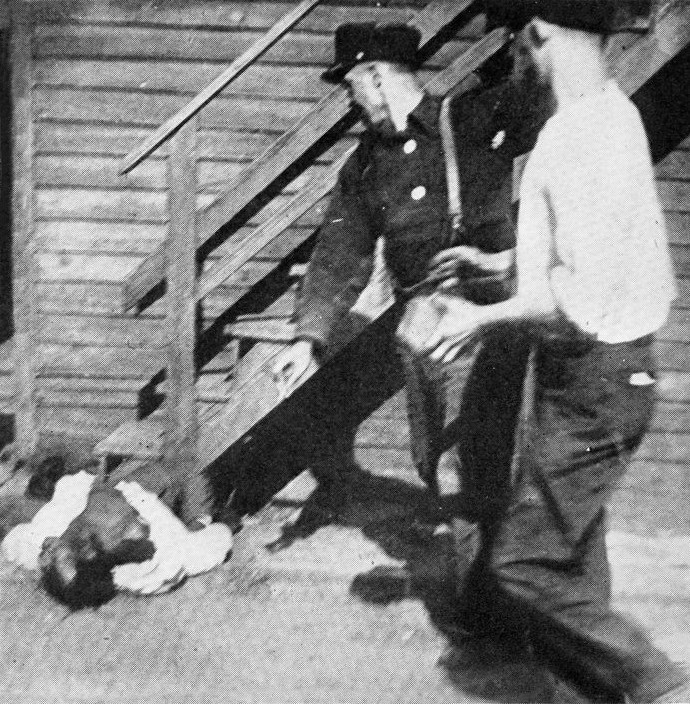

The D.C. riots began when sailors, enraged by the Washington Post’s false report, hunted Charles Ralls. On July 20, they beat Ralls and his wife mercilessly, raining blows with fists and clubs, leaving Ralls with a fractured skull and his wife with a broken arm and deep gashes across her face as they escaped with neighbors’ help as gunshots—bullets tearing through their clothing—followed them to their front door. The police ignored distress calls, and the Post published a front-page call to “join the growing mob,” escalating the violence. Mobs attacked Black residents, dragging them from homes and streets, beating them to death with pipes and bats, their bodies left bloodied and broken, killing at least 15 and injuring 150 with severe lacerations, broken bones, and gunshot wounds. On July 21, a mysterious headline, “Mobilization for Tonight,” hinted at a coordinated escalation, prompting Black self-defense groups. After four days, Wilson deployed 2,000 National Guard troops, but no one was prosecuted, and the Post faced no accountability despite NAACP demands.

Chicago: July 27–August 3, 1919

Six days after D.C., Chicago’s riots erupted at the 29th Street Beach. Eugene Williams’ death sparked a confrontation when police refused to arrest his white assailant, leading to a gunshot exchange that killed a Black man with a bullet ripping through his chest, his body collapsing in a pool of blood. White mobs, inspired by D.C. reports, rampaged through Black neighborhoods, shooting into homes with rifles, bullets shattering windows and piercing flesh, bombing businesses with explosives that tore limbs from bodies, and dumping corpses—some with throats slit and faces unrecognizable from beatings—into the Chicago River. The “Vortex of Violence” on the South Side, an overcrowded Black enclave, was a primary target. Jesse Binga, a Black banker whose success drew a bombing that shattered his home’s walls and left shrapnel wounds on employees, led community defense efforts alongside the 370th Infantry (nicknamed “Black Devils” by German foes), who protected homes. The riots lasted a week, killing 38, injuring over 500 with gunshot wounds, burns, and crushed skulls, and destroying 1,000 homes, with no white rioters charged.

Elaine, Arkansas: September 30–October 3, 1919

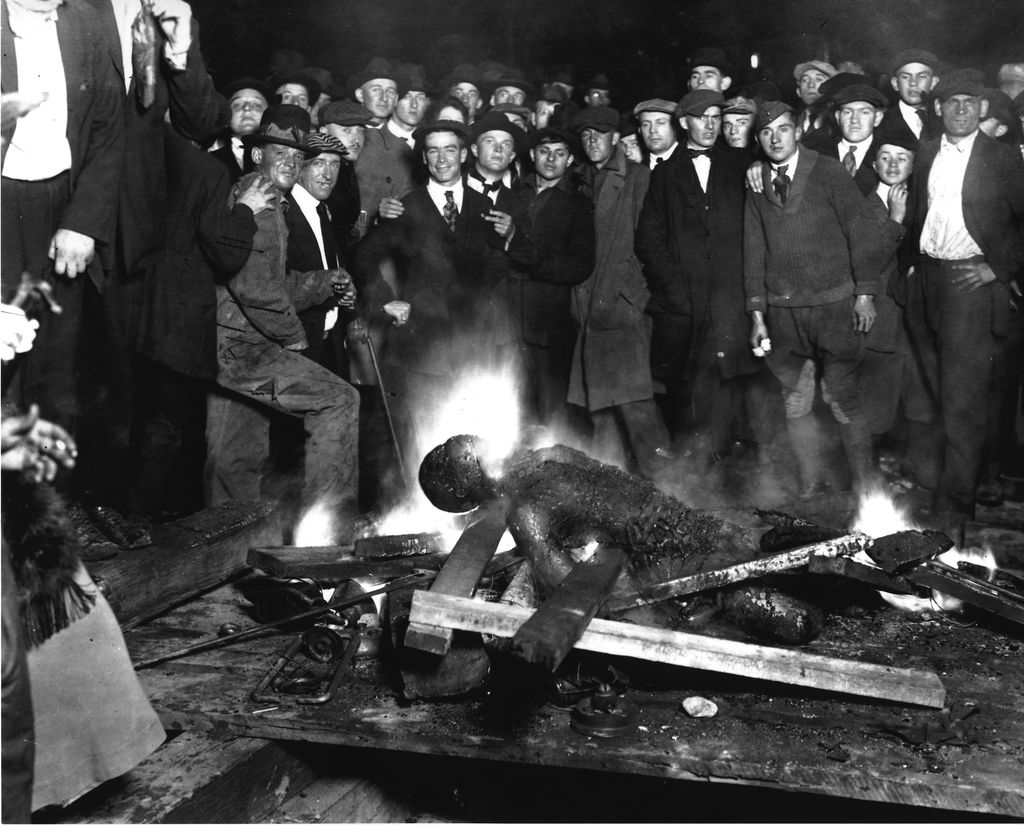

The Elaine Massacre capped the Red Summer’s deadliest chapter. On September 30, Robert Hill’s Progressive Farmers and Households Union met to plan a lawsuit against exploitative landowners. Armed men attacked the church meeting, gunfire shattering windows and spraying glass into the congregation, prompting defensive gunfire that killed a white man with a bullet through his heart. The next day, Sheriff Frank Martin, fueled by anti-communist paranoia, formed a militia with 500 troops to hunt Black union members. They massacred at least 100—possibly up to 230—shooting unarmed groups with rifles, bodies riddled with bullets and left to rot in fields, torturing prisoners into false confessions with beatings that broke ribs and teeth, and staging sham trials that sentenced dozens to death by electric chair, their bodies charred and smoking after execution. Four Black brothers were ambushed and killed en route home, their bodies riddled with shotgun blasts and left in ditches, and mobs lynched others, hanging them from trees with necks snapped and tongues protruding. Martial law ended the violence after three days, but no white perpetrators faced justice.

Aftermath: Devastation and Denial

The Red Summer left a trail of destruction. Across 26 cities, hundreds died, thousands were injured, and countless homes and businesses were lost. Official records underreported deaths—D.C. logged 15, Chicago 38, Elaine 100+—but historians estimate a national toll of 300 to 1,000, reflecting the era’s disregard for Black lives. No white rioters faced convictions, and investigations were minimal. Wilson’s inaction, mirrored by local authorities, set a precedent of impunity.

Communities rebuilt with little aid. In Chicago, the Black Devils’ statue honors their bravery, while in Elaine, a 2019 willow tree memorial was destroyed shortly after planting, symbolizing ongoing resistance to remembrance. The violence reinforced segregation and economic disparities, with Red Summer often reduced to a footnote in history books despite scholars labeling 1919 America’s worst year.

Legacy and Reflection

The Red Summer of 1919 exposed the fragility of racial progress in post-war America. Black veterans and workers, seeking equality after defending democracy, faced a brutal backlash from a nation unwilling to honor their contributions. The lack of accountability—fueled by corrupt leadership, biased media, and systemic racism—left wounds that persist. As Bailey Sarian noted, “Hardly any investigating went into the deaths of so many innocent people,” underscoring the need for truth and healing.

In 2025, 106 years later, the Red Summer remains understudied, with no official death toll established. Efforts like the Equal Justice Initiative’s documentation and renewed calls for historical education offer hope, but justice—through reparations or recognition—remains elusive. This article in our Racial Crimes series urges readers to confront this history, ensuring the Red Summer’s lessons shape a more equitable future.

Sources

- The New York Times. (2019–2025). Articles on Red Summer commemorations and historical analysis.

- Chicago Tribune. (1919–2020). Archival reports on the Chicago riots.

- Equal Justice Initiative. (2019). “Red Summer 1919” report on racial violence.

- Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. (2019). Coverage of the Elaine Massacre centennial.

- National Archives. (2021). Documents on Woodrow Wilson’s administration and segregation policies.

- Bailey Sarian. (2023). “Red Summer of 1919.” Dark History Podcast.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.