On May 31, 1921, the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma—known as “Black Wall Street” for its thriving African American community—was devastated by one of the deadliest racial massacres in U.S. history. Sparked by a fabricated assault claim against a young Black man, Dick Rowland, a white mob, fueled by racial tensions and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, attacked Greenwood, killing an estimated 100 to 300 people, injuring over 800, and destroying 35 city blocks. As we mark the 104th anniversary in 2025, this article in our Racial Crimes series examines the Tulsa Race Massacre’s causes, events, aftermath, and the ongoing fight for justice and recognition.

Historical Context: Tulsa in 1921

Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the early 20th century was a booming oil city, attracting wealth and opportunity. Admitted as a state in November 1907, Oklahoma quickly enacted Jim Crow laws enforcing racial segregation, including segregated rail travel and voter registration rules that disenfranchised most Black citizens, barring them from juries or local office. In 1916, Tulsa passed a residential segregation ordinance, mandating that Blacks and whites could not live on blocks where the majority were of the other race—a law ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1917 but ignored locally for decades.

The Ku Klux Klan, resurgent since 1915, grew rapidly in Tulsa. By late 1921, an estimated 3,200 of the city’s 72,000 residents were Klan members, fostering a racially charged atmosphere. The end of World War I in 1918 saw Black veterans return home expecting civil rights progress, but instead, they faced heightened discrimination and violence. Against this backdrop, Greenwood emerged as a beacon of Black success, a self-sufficient district founded in 1906 that housed affluent professionals—doctors, lawyers, dentists—and businesses like grocery stores, nightclubs, two movie theaters, churches, and a newspaper.

Greenwood: The Rise of Black Wall Street

Greenwood’s success stemmed from necessity and resilience. Excluded from white neighborhoods due to segregation, Black Tulsans built their own community, selecting leaders and raising capital to support growth. By 1921, Greenwood boasted a vibrant economy, earning the nickname “Black Wall Street.” Its prosperity, however, stoked resentment among some white Tulsans, who viewed Black success as a threat. Racial tensions simmered, exacerbated by the Klan’s influence and Oklahoma’s segregationist policies, setting the stage for the violence that erupted in May 1921.

The Spark: The Incident on May 30, 1921

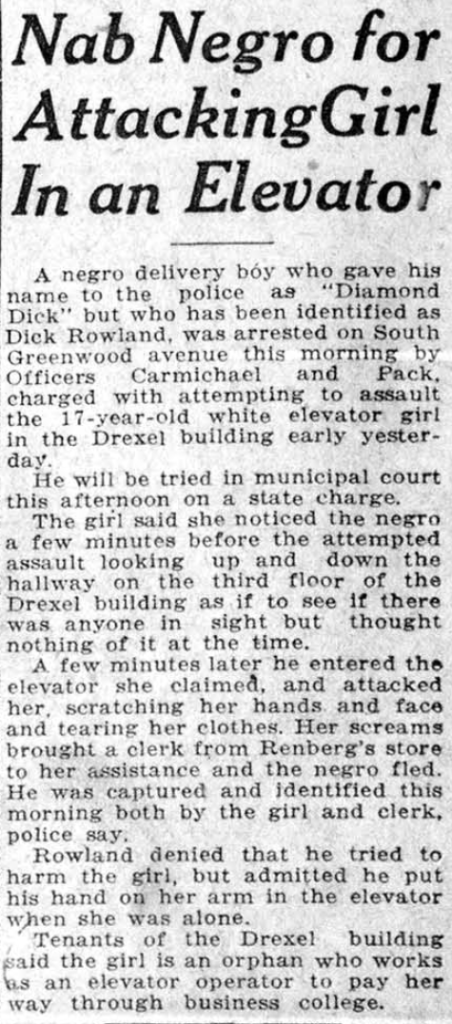

On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner, entered the Drexel Building elevator on South Main Street, likely to use the only restroom available to Black individuals. The elevator operator, Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white woman, screamed during their interaction—possibly because Rowland accidentally stepped on her foot or stumbled into her. A white clerk witnessed Rowland fleeing and Page in distress, prompting a call to the police. Rumors spread rapidly, and despite no evidence, the Tulsa Tribune published a front-page story claiming Rowland sexually assaulted Page, inflaming racial tensions.

Rowland, fearing for his life amid threats of lynching, hid in Greenwood with his mother. On May 31, police arrested him and held him at the Tulsa city jail before transferring him to the courthouse due to threatening calls from white residents demanding his death. By evening, a white mob of over 1,500 gathered outside the courthouse, demanding Sheriff Willard McCullough hand over Rowland for lynching. McCullough refused, barricading the top floor and ordering his men to shoot any intruders.

Escalation: Armed Confrontation

As rumors of a lynching spread, the Greenwood community mobilized to protect Rowland. Around 9 p.m. on May 31, 25 armed Black men, including World War I veterans, arrived at the courthouse to assist the sheriff, reportedly at McCullough’s request—though he later denied this. Witnesses confirmed the sheriff had asked for their presence, but he sent them away, claiming they weren’t needed. Tensions escalated when 75 armed Greenwood residents returned at 10 p.m., facing the growing white mob. A confrontation ensued when a white man demanded a Black man surrender his pistol; the Black man refused, and a shot—possibly accidental—rang out, igniting chaos.

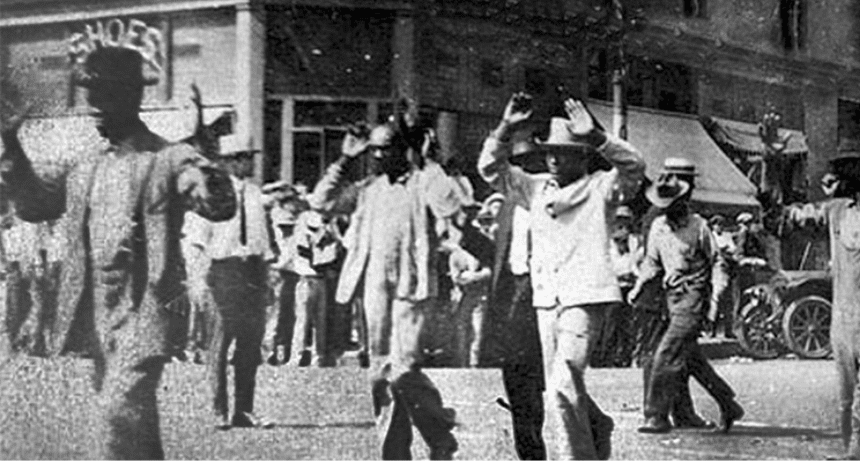

Gunfire erupted between the groups, with the outnumbered Black defenders retreating to Greenwood. The white mob, now armed after looting local stores for weapons and ammunition, pursued them, shooting at Black bystanders indiscriminately, bullets tearing through flesh and leaving bodies crumpled on the streets with blood pooling around them. Some white rioters attempted to break into the National Guard armory for more guns but were unsuccessful. By 11 p.m., National Guard units assembled, deploying to protect white districts adjacent to Greenwood, not the Black community itself. They also rounded up Black Tulsans, detaining them at Convention Hall on Brady Street simply for being Black, with some held for up to eight days.

The Massacre: June 1, 1921

In the early hours of June 1, 1921, the violence escalated into a full-scale massacre. White rioters, including prominent figures like Tulsa founder and Klan member W. Tate Brady, invaded Greenwood on foot and by car, firing into homes and businesses with rifles and shotguns, bullets ripping through walls and bodies, leaving limbs severed and faces disfigured. They threw lighted oil rags into buildings, setting them ablaze, the flames consuming families trapped inside, their screams silenced as roofs collapsed onto charred remains. When Tulsa Fire Department crews arrived to extinguish the fires, the mob turned them away at gunpoint, ensuring the destruction continued unchecked.

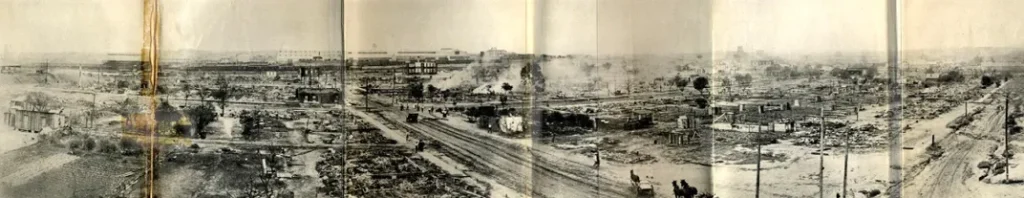

Eyewitnesses reported airplanes—some allegedly carrying law enforcement—flying over Greenwood, dropping “burning turpentine balls” that ignited homes and flesh, and firing rifles at residents below, bullets puncturing skulls and chests, bodies falling lifeless into the streets with blood soaking the ground. A 2015 manuscript and survivor testimonies from later hearings confirmed at least a dozen planes were involved, some privately owned. The violence was relentless: 1,256 houses were burned, 215 looted but not torched, and key community assets—a hospital, library, schools, churches, and businesses—were destroyed. The Red Cross estimated 100 to 300 deaths, with bodies riddled with gunshot wounds, burned beyond recognition, or hacked apart by mobs, though the official tally of 36 is widely considered too low.

Across Tulsa, white families employing Black cooks and servants were coerced by rioters to surrender their employees, who were then detained. By 11:30 a.m. on June 1, Governor James B.A. Robertson declared martial law, deploying 109 National Guard troops. The troops arrested up to 6,000 Black Greenwood residents, requiring them to carry identification cards and holding them at facilities like Convention Hall (now Brady Theater), Tulsa County Fairgrounds, and McNulty Park baseball stadium. Meanwhile, all charges against Dick Rowland were dropped after Sarah Page declined to press charges; police concluded the incident was likely a misunderstanding. Rowland was exonerated, left Tulsa the next morning, and never returned.

Aftermath: Destruction and Silence

The Tulsa Race Massacre left Greenwood in ruins. Over 35 city blocks were destroyed, 800 people were treated for injuries, with many suffering gunshot wounds, burns, and broken bones from beatings, and an estimated 8,000 were left homeless. The economic loss was staggering, with damages later valued at over $1.8 million in 1921 dollars—equivalent to about $30 million today. Despite claims filed against the city, most promised funding never materialized. The Reconstruction Committee delayed rebuilding by enforcing a new fire code banning wooden homes, a tactic many believe was designed to prevent Black residents from recovering. City planners seized the opportunity to rezone “The Burned Area” for industrial use, building the Tulsa Union Depot where homes and businesses once stood.

For decades, the massacre was deliberately suppressed. The Tulsa Tribune removed its inflammatory May 31 article from its records, and police and state archives vanished. No white rioters faced convictions, while the Black community bore the brunt of the violence and loss. Segregation in Tulsa intensified, and the local Ku Klux Klan grew stronger. The event was omitted from history books, untaught in schools, and absent from public discourse until the late 20th century.

Survivors’ Accounts and Early Recognition

Mary E. Jones Parrish, a young African American teacher and journalist, documented the massacre in her book Events of the Tulsa Disaster, the first published account of the riot. As a survivor, she compiled eyewitness testimonies, photographs, and a roster of property losses, preserving a critical record despite pressure from the white community to remain silent. Her work laid the foundation for later efforts to uncover the truth.

In 1996, on the 75th anniversary, a service at Mount Zion Baptist Church—rebuilt after being burned in 1921—marked the first public commemoration, with a memorial placed at the Greenwood Cultural Center. The following year, the Oklahoma state government formed the 1921 Race Riot Commission to investigate. Its 2001 report confirmed 100 to 300 deaths and highlighted the systemic cover-up, recommending reparations and educational reforms.

The Fight for Justice: 2000s to 2025

Efforts to secure justice for survivors and their descendants have faced significant hurdles. In 2003, five elderly survivors filed a lawsuit against Tulsa and Oklahoma, seeking compensation as recommended by the 2001 commission report. Federal courts dismissed the suit, citing the statute of limitations, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal in 2004. In 2007, a bill to extend the statute of limitations for the case was introduced in Congress, reintroduced in 2009 as the John Hope Franklin Tulsa-Greenwood Race Riot Claims Accountability Act, and again in 2012, but it has yet to pass the Judiciary Committee. The bill was named for Dr. John Hope Franklin, a historian and firsthand witness who advocated for recognition of the massacre’s impact.

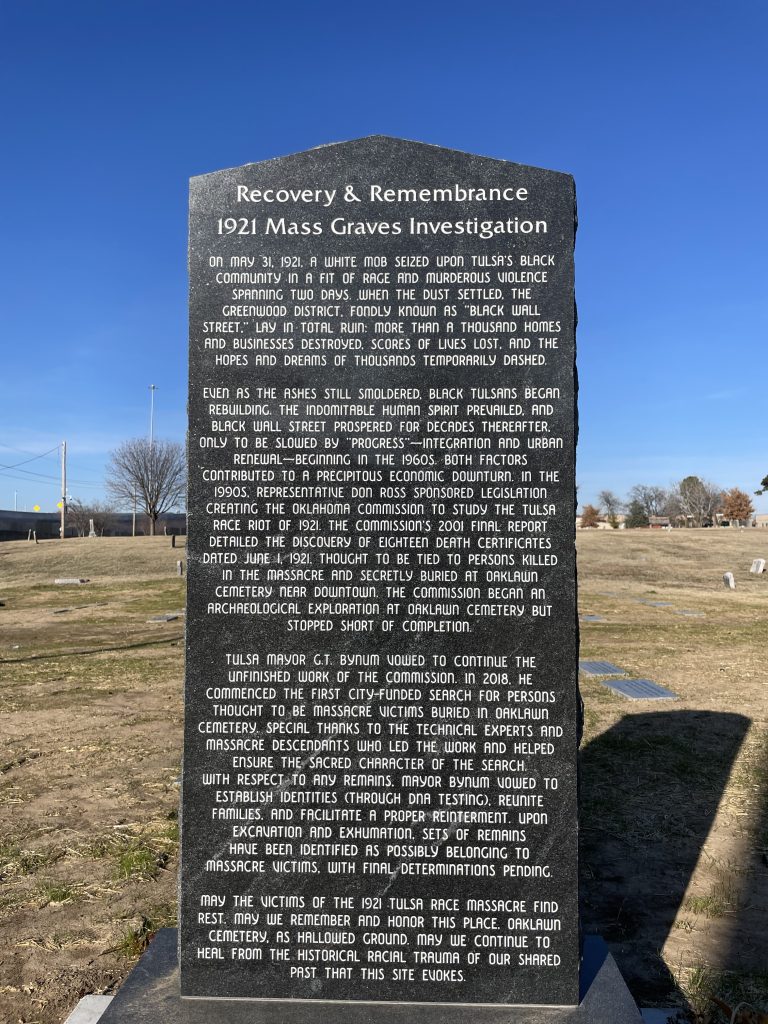

Since 2000, Oklahoma has required the Tulsa Race Massacre to be taught in history classes, with its inclusion in textbooks mandated by 2009. However, a 2012 bill to enforce this statewide failed, with opponents arguing schools already covered the topic. In 2018, the 1921 Race Riot Commission was renamed the 1921 Race Massacre Commission, reflecting a shift in terminology to acknowledge the event’s severity. In April 2020, Tulsa began plans to excavate suspected mass graves in a city cemetery, following long-standing reports of unmarked burials. As of May 2025, these efforts have identified potential sites but no definitive mass graves, per The New York Times.

In 2021, marking the 100th anniversary, three surviving centenarians—Viola Fletcher, Hughes Van Ellis, and Lessie Benningfield Randle—testified before Congress, seeking reparations. Fletcher, then 107, recounted fleeing the violence as a child, while Ellis, a WWII veteran, spoke of the betrayal Black veterans faced after serving their country. Their testimony spurred renewed calls for justice, but legislative action remains stalled. In 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice launched a federal investigation into the massacre under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act, aiming to uncover new evidence, though results are pending as of June 2025.

Legacy and Reflection

The Tulsa Race Massacre remains a stark example of systemic racism and the consequences of unchecked racial violence. Greenwood’s destruction was not just a loss of property but a deliberate erasure of Black success, with effects lingering across generations. The massacre’s suppression from history underscores the need for education and acknowledgment. The Black community built their own successful neighborhood, and it was taken away from them—burnt to the ground, along with their families. This highlights a broader truth: Black Tulsans, including WWI veterans, faced a second war at home after fighting for a country that denied them equality.

Today, efforts to honor the victims continue. The Greenwood Cultural Center and Black Wall Street Memorial stand as tributes, while educational initiatives aim to ensure the massacre is not forgotten. Yet, true justice—through reparations, economic support, and accountability—remains elusive. As we reflect in 2025, the Tulsa Race Massacre challenges us to confront America’s racial history and advocate for meaningful change. For more historical true crime, explore our Racial Crimes series.

Sources

- The New York Times. (2020–2025). Articles on Tulsa Race Massacre excavations and survivor testimonies.

- Tulsa World. (2021). Coverage of the 100th anniversary and ongoing reparations efforts.

- The Washington Post. (2021). Reports on survivors’ congressional testimony and historical context.

- Oklahoma Historical Society. (2001). 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission Report.

- PBS NewsHour. (2024). Updates on the U.S. Department of Justice investigation.

- Bailey Sarian. (2020). “Tulsa Race Massacre.” Murder, Mystery and Makeup Monday.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.